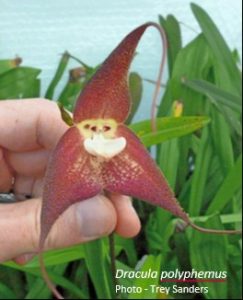

Dracula is a genus of 135 species, distributed from Mexico to Peru. In 1978, Luer established the genus Dracula; before then, they were in the genus Masdevallia. Most of the Dracula species are from Colombia and Ecuador, inhabiting wet, mossy rainforests. Some species are endemic to a single valley or mountain, and because of this, are considered endangered in the wild. Researchers even think that a couple of species could now be extinct in the wild. Seventy-nine Dracula species occur at elevations of between 900 to 2,000 metres, and 38% of these are endemic to this climatic zone. There are a couple of species found at warmer elevations.

I particularly like Dracula because of their unusual flowers, suitability for my growing conditions and because they like to be grown wet. Some of the flowers can attain lengths of 30cm from tail to tail, which make them amongst the largest of all orchid flowers.

The inflorescences on most Dracula are horizontal to pendent, meaning that they emerge and flower beneath the plant. The inflorescences on many species are also sequential, meaning that when one flower has finished the next flower bud will develop and then flower.

As a grower, I always research the climatic and local conditions where my orchids occur naturally because I believe this helps me understand the needs of the plant and will enable me to grow my plant successfully. Of course, I still lose many plants and get it wrong.

photo-Trey Sanders

The things that Dracula seem to need most is humidity, cool to chilly evenings, shade and a lot of quality water. I place my Dracula orchids in a net pot or in a wooden basket and sit the baskets or pots in a tray of water. This not only prevents the plants from drying out, but also increases the relative humidity. Once I see an inflorescence emerging, I take the basket or pot out of the water and hang it up. Be careful when watering while there are spikes, as the smallest drop of water on the end of the spike will cause the spike to rot. High humidity and constant water prevents black leaf tips and prevents the spikes and flower buds from aborting; however, when growing plants at humidity levels above 90%, as I do, air circulation is essential to prevent rotting new growths. Inflorescences will sometimes ‘sit there’ and wait for the relative humidity to reach a certain level before growing further.

I find that Dracula species are better suited to a greenhouse than indoors because of their cultural needs. Dracula need a lot of shade and do not like bright light. There needs to be a considerable difference between day and night temperatures. A good way of knowing whether the temperature is right for the plant is to feel the leaves. Dracula leaves need to be cool to cold to the touch.

I use a mixture of 80% sphagnum moss and 20% coarse perlite in the baskets. The humidity provides essential humidity to the roots and soaks up water quickly.