An edited and updated transcript of a talk given to the Orchid Study Group in 2006 by Richard Morris

(Edited by Kevin L. Davies, who also supplied additional notes and updated the orchid nomenclature)

The Family

Having been invited to come and talk to you today about the orchid house at Penllergare, I have to start with a confession. I know very little about orchids! One thing I have learned is that names given to these plants in the 19th century probably no longer apply, even if the plants themselves still exist. So, any names I give you will be as they were at the time of John Dillwyn Llewelyn’s pioneering efforts, between the 1830s and his death in 1882.

I have been warned that it is quite probable than some of you will not know who John Dillwyn Llewelyn was nor why his orchid house should be so important. He is important for many reasons, not least as a pioneer photographer. His orchid house is famous since it appeared in the very first article published in the Journal of Horticultural Society, now The Royal Horticultural Society, back in 1842.

John Dillwyn Llewelyn, son of Lewis Weston Dillwyn, the famous botanist and one-time owner of the Swansea pottery, and Mary Adams, was born in 1810. Lewis Weston Dillwyn, his father, claimed to have had Welsh ancestors, possibly descending through the Welsh poet Ieuan Dilwyn, who, it is said, wrote some extremely racy poetry. Dillwyn’s great, great, grandfather William had been amongst those who had to flee to America in the 17th century because of their Quaker beliefs. He had settled in what eventually became Philadelphia. One of his children, another John, had a son named William, who at the end of the 18th century returned to Britain, landing at the Mumbles. He bought the lease of the Swansea Pottery and in 1802, he sent his eldest son, Lewis Weston Dillwyn, down to Swansea to take on its management. During this time the pottery produced its finest porcelain, now highly collectable, as well as earthenware for daily use and, in the 1850s, Etruscanware, the clay for which is said to have come from the Penllergare estate

In 1807, Lewis Weston Dillwyn married Mary Adams, the illegitimate daughter of Colonel John Llewelyn of Ynisygerwn and Penllergare. Llewelyn did in fact have a wife but there was no issue from the marriage. Despite Mary being illegitimate, there seem to have been no problems over her marriage to Lewis.

The Dillwyns lived at the Willows in Swansea, now long demolished, and they later purchased Burrows Lodge, which stood behind Swansea Museum, formerly The Royal Institution of South Wales (RISW).

They had six children: Fanny was the eldest and she married Matthew Moggridge. One of their descendants is Hal Moggridge who was involved both with Aberglasney and the National Botanic Garden of Wales. He it was who designed the pathway and rill than runs down to the entrance of the National Botanic Garden, amongst other things. He also worked at Dynevor for the National Trust and is Chairman of the Penllergare Trust restoring Penllergare estate. Next, came John Dillwyn. The second son, William, had died young. Then came Lewis Llewelyn Dillwyn, who was a Magistrate involved with the Rebecca Riots. He served as MP for Swansea for about 40 years. For a time, Lewis Llewelyn Dillwyn was also involved with the Swansea pottery and it was during his tenure in the 1850s that Swansea Etruscanware was produced, his wife Bessie, a daughter of Sir Henry De la Beche, the geologist, designing the pots.

Two daughters followed. Mary, like her elder brother John, was an early amateur photographer. A small album including some of her photos was bought a few years ago by the National Library of Wales for £40,000. She married the Rev. Montagu Earle Welby, one time vicar at Sketty and Oystermouth. Lastly came Sarah or Sally, who died young and whose death scene is shown in a painting by C. R. Leslie in Swansea Museum, with further details in my account for Minerva, The Journal of Swansea History, produced by The Royal Institution of South Wales.

The botanist Lewis Weston Dillwyn wrote a number of books. His first was British Confervae (Algae). Amongst his other publications were A Flora and Fauna of Swansea, produced in 1848 and The Botanist’s Guide through England and Wales, written with his friend Dawson Turner. Dillwyn was also the first President of the RISW and Mayor of Swansea. In 1832, he became a member of the First Reformed Parliament.

Mary, Dillwyn’s wife, was the natural daughter of Colonel John Llewelyn of Ynisygerwn and Penllergare (Note that historically ‘Penllergare’ is the correct spelling, not ‘Penllergaer’). It was the colonel’s intention that, upon his death, these estates should pass to young John Dillwyn on his coming of age and that the latter should adopt Llewelyn as his surname. As a result, John became known as John Dillwyn Llewelyn. When eventually Colonel Llewelyn died, the estates passed to John who had not yet reached his majority and so, a trust was set up under Lewis Weston Dillwyn to manage them.

John was educated privately by family tutors, probably due to his having asthma from an early age. He eventually matriculated at Oriel College, Oxford but left before taking a degree. Upon coming of age in 1831 he took over the running of Penllergare and on 28th March set out on a continental trip that eventually took him to Norway where he was caught up in a cholera epidemic and his return delayed. He arrived home on 10th July 1832, during his father’s campaign to stand as an MP for the First Reformed Parliament.

John’s coming of age was celebrated by a 21 gun salute in Swansea. His father wrote on Tuesday January 11th :

“We all went to a ball at the Veranda. When the clock struck 12 John became of age.”

The next day:

“After supper, the event was marked in a most handsome manner. About 4, Mary and I got to sleep at the Willows and the 3 juniors went in a carriage to Penllergare. The bells of Swansea and Llangyfelach rang all day and at 1 o’ clock 21 guns on the pier were fired. Mary and I went back to Penllergare soon after breakfast and in the afternoon I drove with the two boys and introduced John to the tenants at Llangyfelach where a dinner had been provided on the other parts of the estate. The uncertainty of Mrs Llewelyn’s situation prevented us from having a party at home and only Capt. Jeffreys dined with us. There was a dance in the Hall in the evening”.

The Cambrian for Saturday January 15th noted:

“On Wednesday last, John Dillwyn Esq. of Penllergare attained his majority; on which occasion the tenantry on his estates in Glamorganshire, Breconshire and Carmarthenshire, were regaled with excellent dinners and a liberal supply of the best ‘home-brewed’. The bells of St. Mary’s Church, in this town, were rung merrily throughout the day in honour of the auspicious event”.

In 1833 John was elected to the Athenaeum in London and on 18th June of that year at 11.40am at Penrice Church, he married Emma Thomasina Talbot, the youngest daughter of Thomas Mansel Talbot of Penrice, and Lady Mary, formerly Fox Strangways, a daughter of the Earl and Countess of Ilchester. Emma was a cousin of Henry Fox Talbot, the pioneer photographer. They honeymooned in Europe and whilst there, organised the creation of the mile and a half long drive from Cadle up to Penllergare House. A few letters regarding the construction of the drive survive suggesting that it had become quite a major undertaking.

While they were on their honeymoon, John’s brother Lewis wrote to him at Geneva. He was able to say that:

“The road I think is getting on very well, the stones are put on from Cadley side of the Primrose Meadows to about half way through Nidfwch Wood – Your garden is looking beautiful, the carnations and dahlias are quite splendid, so much so that I go down always twice, sometimes three times a day, for the sole purpose of looking at them”.

John’s parents were, however, somewhat concerned about the amount of work needed to construct the road and also its cost.

Works also began on the formal gardens and restoration of the house. In its heyday, Penllergare was famed worldwide for the botanical expertise of John Dillwyn Llewelyn, obviously aided by several excellent gardeners. In the walled garden he grew exotic plants: pineapples, tea etc – the latter, he said jokingly, to put Mr. Twining out of business. Within the walled garden lay the orchid house which in later years, fell into disuse and disappeared beneath the undergrowth.

Having married a descendant of the Llewelyn family, sometime in the 1970s I became interested in the estate and in John Dillwyn Llewelyn. Furthermore, I discovered his interest in botany and especially his interest in orchids.

The Orchid House

As early as October 1836, a mere three years after John’s marriage, we find that he was in contact with the Botanic Gardens Kew regarding the possibility of subscribing to an expedition to collect orchids.

Later, in June or July 1886, some four years after the death of John Dillwyn Llewelyn, A. Pettigrew of Cardiff, who was gardener to Lord Bute and writing for The Journal of Horticulture and Cottage Gardener, visited Penllergare and was shown round by John’s son, John Talbot Dillwyn Llewelyn. Pettigrew had this to say about the orchid house:

“After leaving the Melon ground with its many objects of interest, we were shown through the forcing and plant house. The first of these, a lean-to greenhouse, was furnished with a good selection of tuberous begonias, vallotas, pelargoniums, and a choice of cool orchids. The roof was partly covered by a large plant of Lapageria alba, which grows vigorously and flowers freely, the flowers lasting for a long time in perfection before fading. Next to this is an Orchid house, which contains a rich collection of well-grown plants, clean and healthy. Mr Llewelyn is a good orchidist, and perhaps it would not be too much to say that he inherits his love for them from his late father, who was deeply interested in their introduction and cultivation, that he and another gentleman employed a collector of Orchids between them long before Orchideæ became so common in this country.

The following are a few of the varieties that were in favour or throwing up spikes at the time of my visit – Cypripedium barbatum (now Paphiopedilum barbatum), C. Lowi (now Paphiopedilum lowii), C. niveum (now Paphiopedilum niveum), C. caudatum (now Phragmipedium caudatum), C. Pearcei (now Phragmipedium pearcei), C. superbiens, (now Paphiopedilum superbiens) C. Lawrencianum (now Paphiopedilum lawrenceanum), C. Parishi (now Paphiopedilum parishii), C. concolor (now Paphiopedilum concolor), C. hirsutissimum (now Paphiopedilum hirsutissimum), C. venustum (now Paphiopedilum venustum), C. purpuratum (now Paphiopedilum purpuratum) and C. Stonei (now Paphiopedilum stonei). In closed proximity to the latter was a large plant of Peristeria elata throwing up five spikes of great strength, and five large clumps of Dendrobium nobile in 14-inch pots, each pot having a little forest of pseudo-bulbs. Besides these there were fine pieces of D. Dalhousianum (now D. pulchellum), D. Wardianum (D. wardianum), D. macrophyllum (now D. anosmum), D. pulchelum (D. pulchellum), and others growing in boxes 2 feet square. There were also good pieces of Aerides odoratum, A. crispum and a large plant of A. odoratum purpurascens, with seventy spikes, Phalænopsis grandiflora (now Phalaenopsis amabilis), Vanda Cathcarti (Vanda cathcartii but later Arachnis cathcartii), Phaius maculates (now Phaius maculatus), Dendrobium filiforma (probably Dendrochilum filiforme), Oncidium ampliatum with strong spikes 2 feet long. Besides these, there were large batches of Calanthus (Calanthe) and other winter flowering varieties, some large plants of Eucharis, strong and healthy, and a few specimen Pitcher Plants”.

In 1927, John Talbot Dillwyn Llewelyn, by then Sir John, died. The Orchid Review for the August of that year wrote:

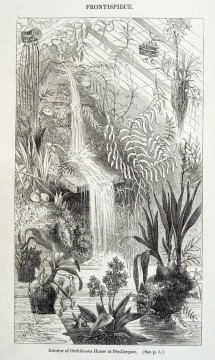

“We much regret to record the death, which occurred on July 7th, of Sir John T. Dillwyn-Llewelyn, Bt., in his 92nd year. Born on May 25th 1836, he was the only son of Mr John Dillwyn-Llewelyn F.R.S., of Penllergaer, [sic] one of the earliest Orchid amateurs. It was Schomburgk’s graphic description of explorations in British Guiana that induced Sir John’s father to construct a special house for the cultivation of Orchids. An account of this structure was communicated to the Horticultural Society of London in 1845 and published in the Society’s Journal, together with the illustration herewith reproduced. [the waterfall]. Schomburgk’s description of a small island whose vegetation had ‘that peculiar lively appearance which is so characteristic in the vicinity of cataracts, where a humid cloud, the effect of the spray, always hovers round them’ was followed by Mr Llewelyn, for he caused water to fall over rough pieces of projecting rock, thereby producing a misty spray. The pipe conveying the water was so arranged that it passed through the boiler fire in order that the temperature of the house should not be injuriously lowered.

The presence of so much atmospheric moisture marked a great advance on previous methods of cultivation, for Mr. Llewelyn stated that the plants have a wild luxuriance about them that is unknown to the specimens cultivated in the ordinary manner. Different species intermingle in a beautiful confusion, Dendrobium, Camarotis and Renanthera side by side, with wreaths of flowers and leaves interlacing one another, and sending their long roots to drink from the mist of the fall, or even from the water of the pool beneath. It was in this house, in the year 1839, that the first flowers of Læloa majalis (grandiflors) (Laelia majalis grandiflora – now Laelia speciosa) were produced under cultivation.

This old-time collection was for a long period maintained by the late Sir John Dillwyn-Llewelyn, who was never more happy than when relating little incidents concerning the early days of Orchid collecting. He was justly proud of the fact that a plant of Aërides affine (now Aerides multiflorum) once carried more than eighty flower spikes, and of a similarly fine specimen of Saccolobium guttatum, (now Rhynchostylis retusa) and believed that these were the first Orchids ever placed before a photographic camera.

Many of the plants were obtained from collectors sent abroad by his father and by Mr Bateman, while others were procured from Loddiges of Hackney. They comprised various Stanhopeas, Oncidium species, Peristeria elata, Phalænopsis amabilis, Cypripedium insigne (now Paphiopedilum insigne), Dendrobiums, Vanda cœrulea and V. teres (now Papilionanthe teres), as well as Calanthe vestita and Catasetums”.

I have skipped ahead a bit, but to read a visitor’s first hand account of the orchid house and its contents is tantalizing especially since so little remains today. Reports such as these, letters, other surviving documents and a few photographs and watercolours, enable us to re-assemble the old orchid house and gives us some idea of the plants it once contained. I am indebted to the late Dr. Paddy Woods and his wife Jennifer, who was born at Penllergare, for helping me to sort out the species list, which has since been updated. Elizabeth Whittle wrote in Historic Gardens of Wales. CADW:

“Perhaps the saddest Welsh loss is the pioneering orchid house built in 1843 by John Dillwyn Llewelyn at Penllergare. It was an epiphyte house for non-terrestrial orchids. In it, he attempted to create a tropical landscape, based on the Essequibo rapids, where one of the orchids he wanted to grow, Huntleya violacea (now Bollea violacea), had been discovered. Above a central pool, hot water splashed down in a series of rocky ledges, creating a hot, steamy atmosphere. The orchids flourished and visitors were amazed by their ‘wild luxuriance’. Now all that remains is an untidy and overgrown jumble of stone. Thirty years later, an orchid house was a standard element in the grander garden.

Construction of the Orchid House

For me the most exciting discovery on the estate is the remains of the Orchideous House. I was told about it on a visit to the Linnean Society, of which John was a Fellow. He was also a Fellow of the Royal Society and a Fellow of The Horticultural Society. No memories of this building now remain and those few who had worked at Penllergare before its sale were confident that it was sited next to the house itself. However, there appears to have been some confusion here since the conservatory, situated next to the house, also contained some orchids. Furthermore, there was no obvious indication of its location on any map. This was not surprising, considering that the estate had been vacant for over fifty years.

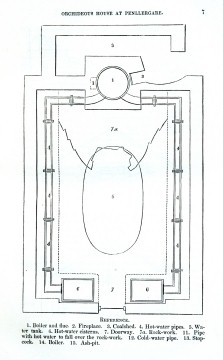

As mentioned earlier, The Orchid House had been the subject of the very first article in the Journal of the Horticultural Society back in 1846 and this article had included several illustrations showing its appearance at the time. The article, written by John himself, appeared under the heading of Original Communications.

“1 – Some Account of an Orchideous House, constructed at Penllergare, South Wales. By J. D. Llewelyn, Esq. FHS.

Communicated October 28, 1845”

[“Mr Llewelyn having mentioned to the Vice-Secretary that he had constructed an epiphyte house, through which a waterfall had been directed so as to dash over rocks, and finally to flow into a basin forming the floor of the house, that gentleman was solicited to favour the Society with some account of it, which he has done in the following interesting communication, accompanied by an interior view of the house, which forms the frontispiece of the present volume”.]

“I enclose with this the ground-plan and section of the stove, which I promised to send. These will show the size and shape of the building, and the arrangement of its pipes and heating apparatus, and the manner also in which the water for the supply of the cascade is conducted to the top of the house by means of a pipe communicating with a pond at a higher level. This pipe is warmed by passing with a single coil through the boiler, and terminates at the top of the rock-work, where it pours a constant supply of water over three projecting irregular steps of rough stone, each of which catches the falling stream, dividing it into many smaller rills and increasing the quantity of misty spray. At the bottom, the whole of the water is received into the pool which occupies the centre of the floor of the stove, where it widens out into an aquarium ornamented with a little island overgrown like the rock-work with Orchideæ, ferns, and lycopods.

The disposition of the stones in the rock-work would depend much on the geological strata you have to work with: in my case they lie flat and evenly bedded, and thus the portions of the rock-work are placed in more regular courses than would be necessary in many other formations. In limestone or granite countries, designs much more ornamental than mine might, I think, be easily contrived.

The account of the splendid vegetation which borders the cataracts of tropical rivers, as described by Schomburgk, gave me the first idea of trying this experiment. I read in the Sertum Orchidaceum his graphic description of the falls of the Berbice and Essequibo, on the occasion of his first discovery of Huntleya violacea. I was delighted with the beautiful picture which his words convey, and thought that it might be better represented than is usual in the stoves of this country.

With this view I began work, and added the rock-work which I describe to a house already in use for the cultivation of Orchideous plants. I found no difficulty in re-arranging it for its new design and after a trial now of about two years can say that it has entirely answered the ends I had in view.

The moist stones were speedily covered with a thick carpet of seedling ferns, and the creeping stems of tropical lycopods, among the fronds of which many species of orchideæ delighted to root themselves.

Huntleya violacea was one of the first epiphytes that I planted, and it flowered and throve in its new situation, as I hoped and expected. The East Indian genera, however, of Vanda, Saccolabium, Aerides, and other caulescent sorts, similar in habit and growth, were the most vigorous of all, and many of these in a very short time only required the use of the pruning-knife, to prevent their overgrowing smaller and more delicate species.

Plants that are grown in this manner have a wild luxuriance about them that is unknown to the specimens cultivated in the ordinary manner, and to myself they are exceedingly attractive, more resembling what one fancies them in their native forests – true air-plants, depending for their subsistence on the humid atmosphere alone.

Different species thus intermingle together in a beautiful confusion, Dendrobium, and Camarotis, and Renanthera, side by side, with wreaths of flowers and leaves interlacing one another, and sending their long roots to drink from the mist of the fall, or even from the water of the pool below.

Many species are cultivated upon the rocks themselves, others upon blocks of wood, or baskets suspended from the roof, and thus sufficient room is secured for a great number of plants. At the same time the general effect is beautiful, and the constant humidity kept up by the stream of falling water suits the constitution of many species in a degree that might be expected from a consideration of their native habits; and I would strongly recommend the adoption of this or some similar plan to all who have the means of diverting a stream of water from a level higher than the top of their stove.

This, I think, in most situations might be easily contrived. My own house lies on high ground, and the water is brought from a considerable distance, but yet I found very little of difficulty or of expense in its construction; for it must be borne in mind that a small quantity of water is sufficient, and that this, after passing through the stove, might be conveniently used for garden purposes.

It must be remembered also that this plan may be added to any existing stove, and that the sole expense will be for the pipe to conduct the stream, and for the labour of the carriage and arrangement of the rock-work”.

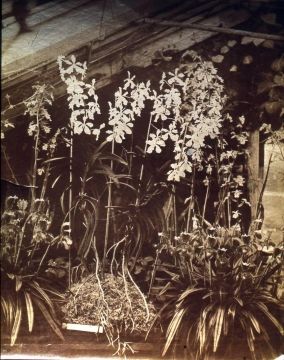

The only other clues for the appearance of the orchid house came from a watercolour of its interior by George Delamotte from 1849 and a faded albumen photographic print from the mid-1850s, presumably taken by John himself, showing some of the plants and bits of roof construction.

It seems that the stove was not home only to orchids since on December 14th 1839, John’s brother, Lewis Llewelyn Dillwyn wrote in his diary:

“Saw some topical birds that John has got from Liverpool & has turned into his stove”.

A Fortunate Discovery

Naturally, curiosity made me want to find the site. The late Sir Michael Dillwyn-Venables-Llewelyn had said I could wander round the estate as I wished. Moreover, my wife and I had been on a Gower Society walk through the Valley. Even so, nowhere was such a building to be seen. Everything was so overgrown, and the estate so large, that it would perhaps have taken a miracle to find it. The all-important clue, missed at the time, was that it was situated on high ground. However, ramblers never visited that area as it was not on the usual circuit of accessible paths.

In 1989, I received a letter from a couple who lived in the Lower Lodge. They had recently moved there and restored the building and curiosity had compelled them to explore the woodlands and other areas. In so doing, they had come upon a large copse of trees, situated on high ground, within site of the dual carriageway, and beneath the undergrowth had found a high stone wall and the remains of buildings. Their curiosity thus aroused, they eventually contacted me and, though I had no knowledge of a walled garden, I asked some questions pertinent to the appearance of the orchid house. Their answers intrigued me and I finally decided that they must have discovered the building. Subsequently, they were sent copies of illustrations from the Horticultural Society article which seemed to confirm matters. However, there were still sceptics who believed that the site was elsewhere, including a former tenant of Penderi Farm who had known the Estate since the 1920s and another who had worked there until 1936. What they probably recalled was the Conservatory that was attached to the main house and had also held some orchid plants and was heated. Further evidence that we had indeed found the orchid house comes from an entry in Lady Mary Cole’s diary for Friday January 12th for 1838. There, she states that she went to Penllergare for John’s birthday. The next day, she:

“Walked to see the Epiphytes.”

Although she does not state that the epiphytes grew in the orchid house, the fact that she “walked” suggests more than visiting the conservatory which was attached to the house. Further investigation showed that the orchid house had been used to grow camellias in later years, which is probably why no living person would have remembered it an as orchid house.

My first visit was in the rain, but it was enough. There was no doubt that this was the building. The next step was to establish its importance, especially as a proposed development was threatening to destroy the site. The then Curator at Kew responded to one of my letters. He wrote:

“The discovery of the footings from the Penllergare ‘Orchideous House’ is obviously of considerable interest to garden historians. I believe that this house marked a significant advance in the creation of landscaped interiors”.

Edward Diestelkamp, from the National Trust, wrote: “I was very interested to learn you think the remains of John Dillwyn-Llewelyn’s conservatory still survive. I believe Dr. Elliott of the Royal Horticultural Society is very well qualified to stress the importance of this conservatory [sic], and the influence it had on nineteenth century conservatories. The romantic ‘wild’ interior influenced later conservatories and it was widely described and illustrated in horticultural journals throughout Europe”.

Carlton B. Wood, a 1989-90 Martin McLaren Fellow, also refers to it in his thesis for the Planning Unit, Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. He refers to it as ‘unique’. In a letter he wrote:

“First and foremost, Mr Llewelyn’s orchid house appears to be one of the earliest (if not the first) documented glasshouse displays in Britain which attempted to recreate the naturalistic feel of a tropical landscape…… Thirdly it appears that Mr Llewelyn was quite a knowledgeable man when it came to the culture of orchids. He was one of a handful of men who used nature as his guide when it came to creating environments in which orchids might flourish…. The other important aspect of Mr Llewelyn’s orchid house is the role it played in influencing other horticulturists. It was featured in the 1846 Journal of Horticulture,1850 Gardeners Chronicle and Agricultural Gazette and the 1856 Cottage Gardener and Country Gentleman’s Companion”.

Dr. Brent Elliott also refers to the building in his book Victorian Gardens. Surviving correspondence provides further evidence of the building and the acquisition of the plants and also underlines Mr. Carlton Wood’s belief in Llewelyn’s knowledge of the subject.

Furnishing the Orchid House

In 1835, John embarked on a great spending spree when he visited his father, Lewis Weston Dillwyn, in London. He arrived in Bath on Thursday March 19th from Swansea and wrote to Emma who was staying with one of her family at Penrice.

“I started this morning from Swansea about 5 o’ clock… We had remarkably fine weather for the Passage tho’ the breeze was so slight that we were obliged to have recourse to rowing and spent 1½ hours upon the water ‑ As we passed Miller’s garden I halted according to my plan and, leaving my Portmanteau at a turnpike close by, issued forth full of horticulture. ‑ I soon found a guide and rambled about in the midst of a terrible scene of temptation ‑ however I have only bought 8 plants… My prudence was sorely tested by 1000 other things but it held out. ‑ and I escaped with no further loss (of money) or acquisition (of plants)

My Botanical smattering came of some use to me as I was enabled to name some of Miller’s unnamed plants for him and to tell him some things which he did not know before… It is rather curious that at the commencement of my horticultural Rambles this morning, the very first thing I received was a parcel that was lying for me at the Coach office and which proved to be the notice of my admission to the London Horticultural Society ‑ I took it as a good omen………”

Miller also assisted Lewis Weston Dillwyn with the gardens at Sketty Hall.

Having arrived in London, John started his rounds of horticulturalists. He dutifully wrote home on Friday 20th March 1835 that:

“…I think that in speaking yesterday of Miller’s garden I passed it over in rather an unhandsome way and did not sufficiently describe how much I was pleased. It is indeed very fine ‑ among other things that he had in bloom ‑ there was the Scarlet Rhododendron arboreum and a crimson mule [hybrid? – ed.] one all dotted over with black (like the figure in Sweet of Russellianum); it was a thick bush 5 or 6 feet high and covered with blossoms !!!!!!! ‑ then his house full of camellias was in great beauty ‑ and a collection of Banksias and Dryandras, many of them in flower proved a sore temptation ‑ His Orchis store too was to me peculiarly interesting from the number of new and unnamed species which he has lately imported from Demerara ‑ several of his sorts were in bloom, some very splendid and all very curious ‑ But you know that I am mad about the Orchis tribe, and my present expedition is, I fear, likely to add full to the mania”.

Monday afternoon, 23rd March 1835, he wrote:

“Monday Athenaeum 5½ o’ clock – The day has turned out very fine and we have paid our intended visit to Loddiges. You will easily guess that I was much delighted, and I dare say will not be astonished when I confess to a little extravagance ‑ I spent there in all near £10 and, among other things, I got Erica Aitonia which I remembered that you particularly admired and of which Loddiges have fine plants for 3/6. I also bought 2 plants of the beautiful new Chinese Paeonia, white with a dark spot at the claw of each petal ‑ one for your mother who I know particularly admires it but the expensive part of my day’s work was the Orchises of which I bought 7 beauties ‑ Ever yours J.D. Ll”.

John and his father also went to Knight’s Nursery as he recalls in part of his letter:

“Knight has a fine collection of plants and my prudence was again put to a sore trial. I, however, did not buy to any great amount excepting perhaps in the item of orange trees, of which he, and he alone of all London nursery men, has any fine collection. I bought six for my own little Emmy and she shall have them under her own exclusive charge. His collection of Orchises is very fine and I bought a few at a very cheap rate. Owing to my engagement with Mr. Traherne, I was obliged to leave the Garden in a hurried way, and, as I could not see Knight before I went, I must return again tomorrow …….”

Wednesday afternoon ‑ 3 o’ clock:

“I have just returned from my second visit to Knight’s nursery garden, which I was obliged to make principally for the sake of giving the necessary directions about sending my different sort of plants off. For example, the orange trees must travel per waggon and the Orchises per coach. I bought a green and a black tea tree which, as they only cost 2/6 each, I intend to turn to good account and close my dealings with Twining”.

Saturday 28th March:

“The next morning ‑ yesterday ‑ we met John Traherne (the Revd J. M. Traherne of Coedriglan –ed.) by appointment at the Athenaeum and went together to see the horticultural gardens. On our way we stopped for a little while at Lee’s – a garden that ought to be seen before and not after Loddiges’ and Knight’s as there was not much temptation there I escaped pretty easily and only bought Tropaeolum pentaphyllum for 5/- which, as it was a nice plant was cheap. It is selling at 10/6. We then proceeded to the Horticultural where there was no temptation again, as of course all their grapes must be sour to a member so young as I. I however hope to make an interest for myself ere long and to get my finger in their pyes [sic]. I particularly looked out for the plants that you mentioned and found them all growing against the wall in great luxuriance, tho’ of course they were not yet in blow. There were also many new things which I must wait to tell you of untill [sic] I see you again which will I suppose be on Wednesday..”

“After returning from the Horticultural Gardens, I went to the Linnean Society and was there introduced to the Librarian, Mr David Don, an eminent man in the Botanical World”.

The references to the purchase of orchids is interesting, and would indicate that by 1835 John was already cultivating them. The first reference to any building occurs in a letter dated Friday 29th July 1836 to his father.

“… My own garden [at Penllergare] is just beginning to put on its autumnal gaiety ‑ but the wet weather which is favourable to the growth of the Dahlias spoil all their flowers, and my hopes for the approaching horticultural show are but small. The stove has a great promise ….”

“The back of the stove which I had left unfinished, in doubt whether to turn it into a common shed, or another stove, I have now determined on glazing. It will be only small and entirely given up to Orchis. 100 degrees of heat and an atmosphere saturated with water, is the enjoyment I promise myself and my pets. I intend them to flower then and to rest after the exertion in a dryer and cooler place”.

So here, as early as July 1836, we find mention of a purpose-built edifice complete with heating system.

The Orchid-related Correspondence of John Dillwyn Llewelyn and family

In the archives of the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew is a letter written by John Llewelyn from Penllergare on October 25th 1836 to William Jackson Hooker, Director of that institution, referring to a forthcoming expedition to Brazil by Mr George Gardener. It reads:

“Sir, At page 226 of the first volume of the companion to the Botanical Magazine, and again at the commencement of the second volume, I find a notice of an expedition to the Brazil mountains undertaken by Mr George Gardener who proposes to offer collections of the flora of that country to those who may subscribe for them – Now though the terms for dried collections are there mentioned, the particulars of the subscription for seeds and plants are not specified, nor is the place or manner mentioned in which application for shares should be made, and I trust that my wish to procure this information will be sufficient excuse for this trespassing upon your time.

It is orchideous plants, in which the district Mr Gardener proposes to explore, is so rich, that I should be most anxious to procure, and as they can be transported with greater ease than most other plants. I suppose that he contemplates sending home the living pseudo-bulbs for distribution”.

A second letter by John from Penllergare to Hooker, dated December 16th (but without year though filed with the 1841 correspondence) again refers to the expedition to Brazil:

“My dear Sir Some time ago you were kind enough to write on my behalf to Mr Gardener who was then collecting in Brazil and thus, through your means, my collection of Epiphytes has been enriched by a great number of very interesting species, some of which have already flowered and many others will do so in all probability in the course of the ensuing Spring.

Now if among them any should prove new species or such as have not been already figured in the Botanical Magazine, and these could be of any service to you, it would give me great pleasure to send, as they appear, either the flowers themselves of drawings of them…

…at this moment there are none of Gardener’s plants of any peculiar interest in blow – but I have a spike of the pretty Guatemalan Epidendrum Skinneri (now Barkeria skinneri) in flower and many of the species from the islands of the Indian Archipelago which I received from Cumming grow and flower freely in my stoves any of which as they blow would be entirely at your service.”

On December 22nd 1841, John wrote again to Hooker enclosing flowers of Epidendrum Skinneri together with a sketch, as promised in the previous letter.

“I send with this the flowers of what I take to be Epidendrum Skinneri, and as the plant is as yet too small to send any portion of its bulbs, I have enclosed a rough sketch of its mode of growth, which will perhaps be sufficient to enable you to judge of the species.

It was given to me in the Summer of this year by Mr. Bateman who has just received it through Mr. Skinner from Guatemala. It has been attached to a rough log of Elder wood with a little sphagnumtied round its roots, and in this situation seems to do pretty well…

I feel very much obliged by your kind invitation to visit the gardens at Kew and when I am next in Town I shall not fail to avail myself if it”. Unfortunately the picture sent with the letter is not in the file.

In 1842, two further letters were sent from Penllergare to Hooker at Kew. The first, dated January 1842, reads:

“The first flower of the spike of a plant which I take to be an aspasia (Aspasia) has just opened in my stove. It is very different from the species figures at 3679 of the Botanical Magazine and should you think it worth while, I will send the flower spike when it is more expanded. It is a pretty plant…

I have also Brassavola glauca (now Rhyncholaelia glauca) now in blow – certainly the best species of the genus.

I have amused myself with making Daguerreotype portraits of this, and other species, and from their exact accuracy they are interesting, tho’ the want of colour prevents them being beautiful as pictures.”

The second, dated January 24th reads:

“I am sorry that I have at present no better Botanical Daguerreotypes to offer you. I have one of Arides odoratum (Aerides odoratum) which I made in the spring.

Most of my specimens have been given away, and my camera is now undergoing some re arrangements which will, I hope, improve its work.

Should you however consider the enclosed of interest, I shall be very happy to send you other examples as I bring them to greater perfection.

I also send a portion of the Guatemalan plant which I suppose to be an Aspasia. Unfortunately, the Brassavola glauca had already faded when your letter arrived.

I find the Box too heavy for post and send it this day per coach”.

In a letter written on February 3rd 1842, from Penllergare, there is a further tantalising reference to the daguerreotype. No such images survive either amongst family or the archives at Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew but had they done so, they would be amongst the first examples of the process for botanical purposes.

“I can assure you that the Daguerreotype drawing I sent you – cost me much less of time and trouble then you give me credit for having bestowed upon it – and if you consider it of any interest or curiosity, I beg that you will keep it as a specimen of Botanical Photography.

Would the flowers of Phaius bicolor (now Phaius tankervilliae) be of any service to you? I have a plant which is now throwing up a flower spike – which is to me a novelty.”

On March 21st 1842, John again wrote from Penllergare to Hooker at West Park, Kew.

“I send with this two flower spikes from my stove. The one appears to be a variety of…..Catasetum and the other is what I take to be Epidendrum selligerum (now Encyclia selligera). It is very fragrant and certainly a pretty species.

Should you wish it, I can send you drawings of the bulbs and habit of either of the plants. My plant of Phaius bicolor has not yet expanded its flowers.

Do you think that Dr. Horstman could be induced to send living specimens of Orchideæ from Guiana? He would have peculiar facilities for so doing while investigating the country for his hortosicii. (hortus siccus – a collection of dried, pressed specimens –ed.). I have a great interest in these and should eagerly avail myself of an opportunity of getting species from the interior of so interesting a country.”

In the next letter to Hooker, dated April 13th 1843, John expressed his sorrow to learn from Lady Hooker that Sir William has been ill. It too included some orchid specimens.

“I send you with the accompanying box, a portion of my plant of Phaius bicolor and Epidendrum selligerum which I hope will be sufficient to form new plants and to give your artist the character & texture of the leaf. Of Dendrobium macrophyllum, my specimen is as yet very small and with the sketch I can only send a single leaf.

I have also enclosed with the above the flower & bulb of a brown coloured Maxillaria which has been in my collection some time but what its name is or from whence it came, I know not”.

A further letter was written from Penllergare to Hooker on April 2nd.

“I enclosed a drawing made by my wife of the bulbs of Epidendrum selligerum, and also one with a spike of flowers of the Phaius which in my last letter I must have inadvertently called maculatus but which is I believe is bicolor, a species not hitherto figured as I think in the Botanical Magazine and which you may perhaps think worth representing. I also enclose a single flower of Dendrobium macrophyllum, a truly magnificent species and can send drawings of its manner of growth and stems at a future time should you wish and should you find the enclosed sketches sufficient. I also send a spike of Dendrobium crumenatum, a very sweet tho’ not a showy species

Should living plants of any of my collection be acceptable to the Gardens at Kew, it would give me great pleasure to send you their first increase.

I shall be very much obliged if you will let me know how and what Dr. Hostman sends.”

Turning for a moment to Curtis’s Botanical Magazine, early volumes include illustrations of several specimens obtained from Penllergare and mentioned in the above letters.

Plate

3951 Epidendrum Skinneri (Barkeria skinneri)

3962 Aspasia Epidendroides (Aspasia epidendroides)

3970 Dendrobium Macranthum (now Dendrobium anosmum)

4078 Phajus Bicolor (now Phaius tankervilliae)

4163 Eria Dillwynii (Eria dillwynii)

4916 Cattleya Skinneri var. Parviflora (Cattleya patinii)

5667 Laelia Majalis (now Laelia speciosa)

Further references to the stove at Penllergare, appear in the next surviving letter in the Kew correspondence dated May 20th from Penllergare referring to a species of Aristolochia. Sadly, the specimen is not included with the letter.

After a gap of ten months, another letter from Penllergare and dated March 7th 1843 reached Hooker. It reads:

“I send you a piece of one of Cumming’s Erias which is valuable from the great facility with which it submits to cultivation & the profusion with which it bears its flowers.

It flowered in my stove last year and this season is a beautiful object with 7 or 8 bulbs each bearing 2 spikes of flowers, the one I send I select as being least expanded, but is not a fair example of the size or vigour of the plant.

I have now Huntleya violacea (now Bollea violacea) in splendour & Dendrobium macrophyllum (now Dendrobium anosmum) full of promise”.

The next letter to his father is dated November 22nd 1843, three years before the appearance of the article in the Journal of the Horticultural Society.

“… for my part, I am getting again deeply into all my old pursuits, experiments horticultural & agricultural ‑ in the garden especially busy. The orchis house in especial delights me ‑ and the plants in the damp atmosphere of the fall seem to forget their captivity, and spread out their roots in all directions to drink the misty air”.

Together with the Kew correspondence, this would seem proof that certainly by 1843, he had built the waterfall and it was functioning. But there is an earlier clue in Curtis’s Botanical Magazine article number 3962. In referring to Aspasia epidendroides, the author states:

“We have already figured one species of Aspasia (A.variegata) at Tab. 3679 of this work. The present is that upon which the genus is founded, and our specimen was kindly communicated in the early spring of 1842 from the rich collection of Orchideae at Penllergar [sic], by its possessor, Dillwyn Llewellyn [sic], Esq”.

If by the spring of 1842 such a specimen was possible, does that date the newer building to 1841 perhaps?

Indeed, in April 1842, John and his father went to London where they stayed at Hatchett’s Hotel. While there, they dined with Sir E. Wilmot, Robert Brown and Hudson Gurney. On April 23rd, they visited Kew and met Sir J. Hooker, staying with him for three hours. That same year, possibly that very day, John presented four orchids to the Gardens which are listed in the Garden’s Inwards Book for 1828‑46. These appear for the year 1842 as Epidendrum selligerum, Phaius bicolor from the East Indies, Maxillaria sp. and Maxillaria S.America. They also visited the Chiswick Horticultural Gardens and on Tuesday April 26th, “John accompanied Professor Wheatstone to witness some magnificent Electro‑magnetic experiments at Clapham.”

John wrote again to Hooker on March 5th 1849 from Penllergare.

“I sent by yesterday’s post a blossom of a schombergia (Schomburgkia) which seems different from the variety of marginata figured in the Botanical Magazine, & also from the crispa & marginata of Dr. Lindley’s Sertum…

It has the pointed lip of marginata with the growth and general appearance of crispa. I have not the Botanical Register by me to refer to, but have some recollection of a notice there of a species called modulata, which this may probably be…….. or it may perhaps be an intermediate variety that would tend to bring crispa & marginata into one species… At all events, I thought it worth while to trouble you with the specimen and without knowing something of the nature of the plant, it is hopeless to try remedies”.

Of this genus, John was to write many years later from Penllergare (July 16th 1855):

“I have sent off today by rail a spike of Schomburghia (Schomburgkia) which is new to me, and I should feel much obliged if you would be kind enough to let me know what it is.

If the variety should prove a new one, and if you should think it of sufficient interest to insert in the Botanical Magazine, I shall be most happy to furnish you with leaves and bulb.

George Bentham was also a correspondent of the Llewelyns and had stayed with them for the meeting of the British Association in 1848. They would also have met at the meetings of the Linnean Society. In a letter from John dated 10th March 1849, from Penllergare, we again find reference to orchids. That the letter starts “My Dear Bentham” would suggest, in 19th century terms, that they were on close friendly terms

“I have lately had a few Javanese orchids – 2 or 3 Oxida Vandas, Saccolabiums and Cypripedium (possibly Paphiopedilum) which have thrown me into a fresh excess of orchidomania. And as the weather is now cold and ungenial I enjoy a good warming at their stove.

With snow on the ground and a March wind from the N.E,. it is a pleasant thing to get into the hot steaming mist of their atmosphere and fancy oneself in the Valleys of Sumatra or Java.

Mrs Llewelyn begs her best remembrances to Mrs Bentham”.

On March 30th , John again wrote to Bentham, from Penllergare, this time referring to parasitic native plants:

“I am very glad that my plant interests you and I heartily wish that Lathiæa (This is probably Lathraea squamaria – the parasitic toothwort that even today grows at Parkmill – ed.) has charms sufficient to tempt you to a Western tour

It is but a step across the hills and to see you and Mrs Bentham would be a real pleasure to us all. Together we would unravel the roots of the parasite and make a crusade too against my mysterious Rhygomorpha (probably rhizomorphs – subterranean lace-like structures formed by the honey fungus and which allow its spread from tree to tree – ed.)…”

There is also some correspondence from Thereza Llewelyn to Mrs Bentham and a further reference to orchids in a letter dated March 3rd 1857.

I saw a list of Orchises, which bloom in January to February in the Gardeners’ Chronicle in which one, which we have had in bloom for some time in the greatest perfection, is omitted. It is Dendrobium speciosum. Our plant has six long and very handsome spikes in full bloom, on it.

A letter dated December 31st 1850 from Penllergare mentions a rather unusual orchid:

“I have forwarded to you a flower spike of a plant which I procured from one of the Warcewitz’s (Warscewicz –ed.) sales, & which was labelled new Mormodes from Panama. It is a singular & handsome plant, and different from ought that I have seen before.

If you should like to it, I can separate a bulb and this would also exhibit the growth of the species in case you might like to figure it in the Botanical Magazine”.

This was followed on January 12th 1851 with a further letter from Penllergare including a sketch of the Mormodes from Panama.

“I send you herewith a rough sketch of the Panama Mormodes which will, I trust be sufficient for your purpose. It gives a correct idea of the present state of the plant with the leaves all fallen, and a second flower spike rising from the base of the bulb….the foliage throughout last summer exactly resembles that of Calasetum trideatalum (probably Catasetum tridentatum) but it died away as the winter approached and the plant was then placed in a cooler and drier place for the purpose of giving it a season of rest.

The first appearance of its awakening was the weak spike of flowers which I sent to you – and the second which is represented in the drawing appears much stronger & will probably bear a larger number of blossoms – the spike has no tendency to droop like that of Calasetum Warsewitzii, (Catasetum warscewiczii) a plant from the same country which flowered in my stove last summer. It appears to be of an easy cultivation and the peculiarity of its colour and its musky odour will, I think, make it an acceptable addition to its class.

I shall therefore endeavour to propagate it & distribute it as widely as I can.

The first offset I hope shortly to send to Kew”.

The next issue for the 16th of March carries a description of the orchid house and repeats the illustration of the cascade that first appeared in the Horticultural Society’s Journal in 1846.

In the ‘Penllergare Book’, a scrap book put together by John’s daughter‑in‑law Caroline, there is a quote from the Gardeners Magazine of September 21st 1895, written by H Honeywood D’ Ombrain who was a Reverend and, as is Hal Moggridge, a recipient of the VMH.

“… the late Mr Llewelyn was a keen horticulturist, and I believe he was one of the very first who took up the cultivation of orchids and in conjunction with Mr Bateman sent out collectors to the East Indies and other places for the purpose of obtaining and sending home those floral treasures…”

Amongst publications on orchids is one by James Bateman The Orchidaceae of Mexico and Guatamala 1837-1843. This includes an illustration of Laelia majalis (now Laelia speciosa) of which the original watercolour was by Emma Llewelyn.

In the Journal left by Thereza Llewelyn for 1857, she refers to the site of the Orchid House.

“We went up to the Garden, & found ours looking very nice – There are two beautiful orchises now in blow, Dendrobium pulchellum which is a delicate lilac-buff flower, & very beautiful and D. aggregatum which is entirely yellow, the centre being of a darker yellow – The Dendrobiums are one of my favourite sorts of orchises. In the evening, I examined a specimen of Nitella flexis (an alga – ed.) which we have growing in the aquarium, with the microscope; the structure of the seed capsule, is very curious, and in this plant the flow & reflow of the sap is very clearly discernable; it flows up, one side and down the other, without there being any partition between the two currents! – A great number of infusoria &c were with, or growing on the plant, some of which were very beautiful”.

The End of an Era

From photographs it would seem that the Orchid house was still standing together with its roof up to the time that the Welsh Bible College moved onto the estate at the end of the 1930s. The serious vandalism probably occurred during the war years when units of General Omar Bradley’s troops were billeted there. Subsequently the estate was further vandalised.

On March 25th 1928, the walled garden area was rented out as a nursery garden. One of the owners, Mr William Edge, now of Bridgend, recalled some details from those years.

Mr Edge wrote:

“March 1928 we rented the gardens after the death of the first Sir John Llewelyn Bart” (John Llewelyn’s son, John Talbot Dillwyn Llewelyn who had lived at Penllergare).

“We ran a nurseryman etc business for 12 years. We had 12 months notice as the Bible College at Swansea intended to buy the mansion and gardens when they had raised the necessary cash.

Their workmen and students knocked off all the plaster on the outside walls & cemented them all around. They did a lot of painting of the cornices etc in the Library and elsewhere! The deal fell through, the cash was not raised.

Then the war came and the American army took over the House. General Omar Bradley used it as headquarters. When they left, vandals took over, stole lead etc. Finally, a few years later the Territorial army blew up the mansion”.

Mr Edge and his family had lived in the Head Gardener’s House; but the most interesting fact was that he was able to recall the layout of the walled garden area and the Orchid House. How different it was in the day of John Dillwyn Llewelyn cannot be readily established but it is probable that the general layout of paths and pond were as originally designed. Indeed, recent investigations have uncovered the edge stones of the original path system dating back to John Dillwyn Llewelyn’s time

From the various letters, published articles etc, it is possible to have some idea of the construction and contents of the ‘stove’ at Penllergare.

Today its remains, together with those of the walled garden area can be found adjacent to the newly built Bellway homes, a faint echo of a period of enlightenment when Swansea had played such an important role in the history of orchids, their science and cultivation.

At the end of 2007, having previously decided that it was not worth doing so, CADW scheduled the remains of the Orchid House at Penllergare.